“Have you ever attempted to mount some old tower stairway, spiralling up through darkness, and in the heart of that darkness found yourself at the cobwebbed edge of nothing? Or have you followed some coast path, cut along the face of a cliff, only to discover yourself, at a turn, on the jagged verge of a break. The emotional worth of such experience - from a literary point of view - is proved by the force of the sensations aroused, and by the vividness with which they are remembered.”

- Lafcadio Hearn, from his book ‘Japanese Ghost Stories’ (edited by Paul Murray)

Let’s begin ‘without’:

I have spoken previously about some of the pitfalls I, and many other performers face, when resigning oneself to a life “on the stage” (in my very first article, here). I thought it was about time I revisited an aspect of this piece, somewhat older, an still befuddled… someday, I hope, the oven might not be so hot, and I’ll get to place my hand upon it.

Temptation is the silent driver of many tales. Our modern sensibility pushes us to consider the character in question: “Oh Faust! what is he like, eh?”. But an older, and perhaps more clear way of viewing the tales is by considering their themes. Thus, many a classic character, heroes and villains and everyone in-between, become the spirit of certain constant human motivations, reoccurring themes in life, or aspects of reality itself. “Don’t be like Faust” may seem an obvious lesson, but it’s a harder one to heed than one might consider.

Temptation is a helluva drug.

In my own practice, as I have previously explored, the main temptation I face is to burst out of the tale itself and show myself to the audience. I am easily ensnared by laughter, you see, wanting immediately to make more erupt. Given that tales are fixed, the point at which one can make an audience laugh is just that - a point, singular. When the temptation to milk more laughter becomes too potent, I effectively leave the tale. Then, I have noticed, I’m ‘doing a bit’. At this juncture, it’s all ‘me’, and no ‘tale’.

Entertaining? Maybe. Respecting the canon? Hardly… Ok, not at all.

But is this such a great sin? Should I be cast from the Halls of the Oral Tradition for such crimes? This isn’t for me to say, but probably not. A self-imposed stint of probation, characterised by a good deal of reflection and correction is probably the best punishment.

Truth be told, I’m serving such a sentence as I write this!

One of the aspects of this weird mix of ‘hard labour’ and ‘solitary confinement’ is to reflect on the tales themselves, especially tales that include temptation in some form or another.

Mind you, as far as examples to share with you lot goes, I have tried to find tales where temptation does not appear as a central theme. Rather, I have chosen tales that better reflect the daily chore of avoiding, or the daily failure of indulging in, temptation. In my opinion, the sense of ‘the real’ is always to be found in the best tales. Well, for the most part… you’ll see.

So, in that spirit, let’s explore. Go on, you know you want to!

Progressive Malice

The temptation to lie is often borne from envy. There are many tales which highlight this, but I have selected this Arab folktale, popular in Qatar, to share.

Enjoy!

(Collected by Mei ElGindi and Um Khalaf, Guernica Magazine, 2014)

“There was once a man who had a sister and they lived happily alone in their house. He fished and traded and raised sheep, and then returned home to his sister. They enjoyed each other’s company and were happy.

By Allah’s will, the brother came of age. His sister said to him, “O brother, why don’t you get married?”

“I’m afraid to bring home someone who will make you uncomfortable and anxious,” he replied.

“No, my brother,” she assured him. “Our neighbors have a daughter and she is pretty. Insha’Allah she will be a sister to me.”

The man went and proposed to the neighbor’s daughter. By God’s will, they were married and he brought her back home.

In the beginning, the wife got along well with the sister. She loved her and looked after her and they had fun together. But the wife was very jealous and one day a bad intention infiltrated the wife’s heart toward the sister.

Whenever the brother was away on travel or elsewhere, the sister sat at her window in her room and talked to the moon. She said to it, Greetings, father of happiness! O one who gives good company to virtuous girls in their mother’s house.

The sister did this to pass the time, for they had no electricity—nothing except the moon.

On one of these occasions, the brother’s wife overheard the sister talking to the moon. She put her ear against the door to listen as the poor girl talked to the moon:

Greetings, father of happiness!

O one who gives good company to virtuous girls in their mother’s house.

One day, the brother came back from his trading trip and his wife said to him: “Hey, dearest?”

“Yes?” he replied.

“I have something to tell you about your sister. She’s not decent!”

“My sister? What!” he exclaimed. “How is my sister indecent? I raised her very well. And she comes from a good family,” said the brother.

“No,” said his wife. “At night, your sister has company in her room. She sits and chats with him. If you want to hear for yourself, I’ll show you tonight.”

The moon appeared that night, and the sister came in and sat with her brother and his wife. They dined, chatted, and had a good time. Then she withdrew to her room to talk to the moon as usual:

Greetings, father of happiness!

O one who gives good company to virtuous girls in their mother’s house.

The wife called to her husband, saying, “Did you hear? Did you hear how your sister is not a decent girl? But me, I would never do anything wrong.”

But the brother didn’t listen because he believed his sister was a very good girl.

One day, a man came around selling eggs. He advertised them, “Baid al hamara, baid al hamara, baid al hamara!”

The brother’s wife went and bought all the eggs the man had, took them home, cooked them, and gave them to the girl, saying, “Eat! Eat all the eggs!”

The poor girl ate all the eggs, and then her stomach began to bloat, getting bigger and bigger.

Then the wife said to the brother, “See, look at your sister! She’s pregnant! Go now, take her away and kill her and that’s it!”

The brother had no choice. He went to his sister and said to her, “Come, let’s go to the barr,” an oasis in the open desert and a favored spot for picnics.

So they went to the desert and sat under a tree. The sister put her head on her brother’s lap and said to him, “Don’t leave me!”

“No, don’t worry,” he answered. “We will sit here and have a lovely time and drink some coffee, and then we will head back to town.”

So the sister fell asleep. As she continued to sleep, her brother slowly slipped his legs out from under her. He left her there, alone, and went back home.

His wife asked him, “What did you do with her?”

“It’s over. I killed her,” he replied.

The wife was happy with her victory. Now there was no one to compete with her for the brother! By Allah’s will, the wife stayed with her husband.

Far away in the desert, the sister woke up and called out, “Brother! O Brother! Brother!” But she didn’t find him anywhere.

The poor girl gathered herself and sat under the tree. Day after day, her stomach grew bigger and bigger until, by Allah’s will, she gave birth to birds—twelve baby birds from the eggs she had eaten.

The birds grew up and learned their mother’s story. So they flew to the house where their uncle lived with his wife and sat on the windowsill and pecked at the window. The brother’s wife heard them and chased them away: “Kish, kish!” “Shoo, shoo!”

They replied:

“Shoo yourself! O uncle, you confused uncle, you hear the voice of the woman. The poor girl was only pregnant from the bird eggs she swallowed!”

Again the wife said, “Kish, kish!”

They replied:

“Shoo yourself! O uncle, you confused uncle, you hear the voice of the woman. The poor girl was only pregnant from the bird eggs she swallowed!”

The brother heard the birds and said, “Let’s hear what they say.”

“No, they have no story to tell,” said the wife. “These birds just come from the desert; let them leave.”

But the brother heard what they said:

“Shoo yourself! O uncle, you confused uncle, you hear the voice of the woman. The poor girl was only pregnant from the bird eggs she swallowed!”

He decided to follow them.

In the meantime, while the birds were with their uncle, the poor girl remained all alone in the desert. While she was there, a sheikh came along with his rabea, a group of followers.

The sheikh went to the girl and asked her, “Tell me, are you human or djinn?”

He saw the young girl and he liked her. She was pretty and good. The sheikh sat with his rabea, had a nice time, and then they decided to leave.

“No, I am not going anywhere. You go ahead,” said the sheikh to his companions.

“How will you spend the night here in the barr, with no one in your company?” they asked.

The sheikh said, “I’m staying here. You ride off ahead of me!”

They listened, of course, because he was, after all, the sheikh. So they left and he stayed behind.

The sheikh went to the girl and asked her, “Tell me, are you human or djinn?”

“I am human,” she said.

“Human? Then what are you doing here in the barr? What brought you to the desert all alone?” wondered the sheikh.

The girl told him the whole story of her brother’s wife, the story of her brother—how he had brought her there, and about the birds and the eggs. She told him everything.

The sheikh said, “I will marry you and make you mine.”

So he put her on his horse, headed home, and married the girl. She lived the rest of her life in joy.

The brother—led by the birds—returned to where he had left his sister, but he could not find her. The birds flew away, and the brother returned home alone.

Rohna anhoom o jeena o ma atoona sheey: We came and we left, and we took nothing from them”

A little lie, designed to besmirch the reputation of a perceived rival, turns into bigger lies, and then to evil actions. Yes, it all ends up fine in the end, but none of this needed to happen. It gives this little legend, as I prefaced, a greater sense of ‘the real’ - there is no comic book villainy here - the wife is jealous, and all she needed to do was contrive a situation where social taboos needed to be upheld. The fantastical element of the birds is counteracted by the denial of the supernatural from the sister:

The sheikh went to the girl and asked her, “Tell me, are you human or djinn?”

“I am human,” she said.

It makes the tale feel more human, don’t you think? The sister here, again very subtly, avoids the temptation to deceive the sheikh; she could have proclaimed that she was indeed a djinn, and demanded riches - a move one could perhaps expect in a folk tale of this nature. But unlike her sister-in-law, succumbing as she did to temptation, the sister simply states the truth, and is rewarded for it.

Granted, the nature of the temptation in this tale is subtle, perhaps not designed to be focussed on or even considered at all, but that’s exactly why I chose this one - it seems to me to be more indicative of the myriad, real world temptations we allow ourselves to indulge in; “I’ll blame Gary from accounts, nobody likes him anyway”, “I’ll tell my boss I was stuck in traffic, when I actually just slept in late", “Yes, officer, the wallet was empty when I found it" are all little lies. But to live by them is to give in to the same, life-ruling form of temptation that leads to bigger, more baroque lies.

The temptation of the wife in this tale lies in the will to be the sole object of affection. We see the progression I highlighted above: Narcissistic urge, then Sociopathic, then Homicidal.

It’s rare in folktales to see such a subtle progression, all leading from a simple succumbing to an egoic temptation.

Now I Want It More…

There’s an odd thing I’ve found that happens when discussing ‘temptation’ publicly. So often have I encountered this odd thing, in fact, that I’ve felt forced to ask direct questions to ascertain that this strange thing is in fact the case:

“When I say ‘temptation’, do you think of lust?”

Most people do, I find, for whatever reason. Now, I’m not going into a diatribe about ‘these days’, with all the porn, and the worship of glossy magazines (because, apparently, I’m still living in the late 90’s), but you catch my drift, I’m sure. Temptation = Sexy times.

Love is a powerful motivator in the tales, but forbidden love is a more complex theme. Sometimes the nature of the prohibition is unjust, leading to great victories over tyrants, or great tragedies in losing our “star-cross'd lovers” in the end.

Rarely, and in my opinion, more fascinatingly, the prohibition is justified. Then we find the temptation to transgress can lead to monstrous outcomes.

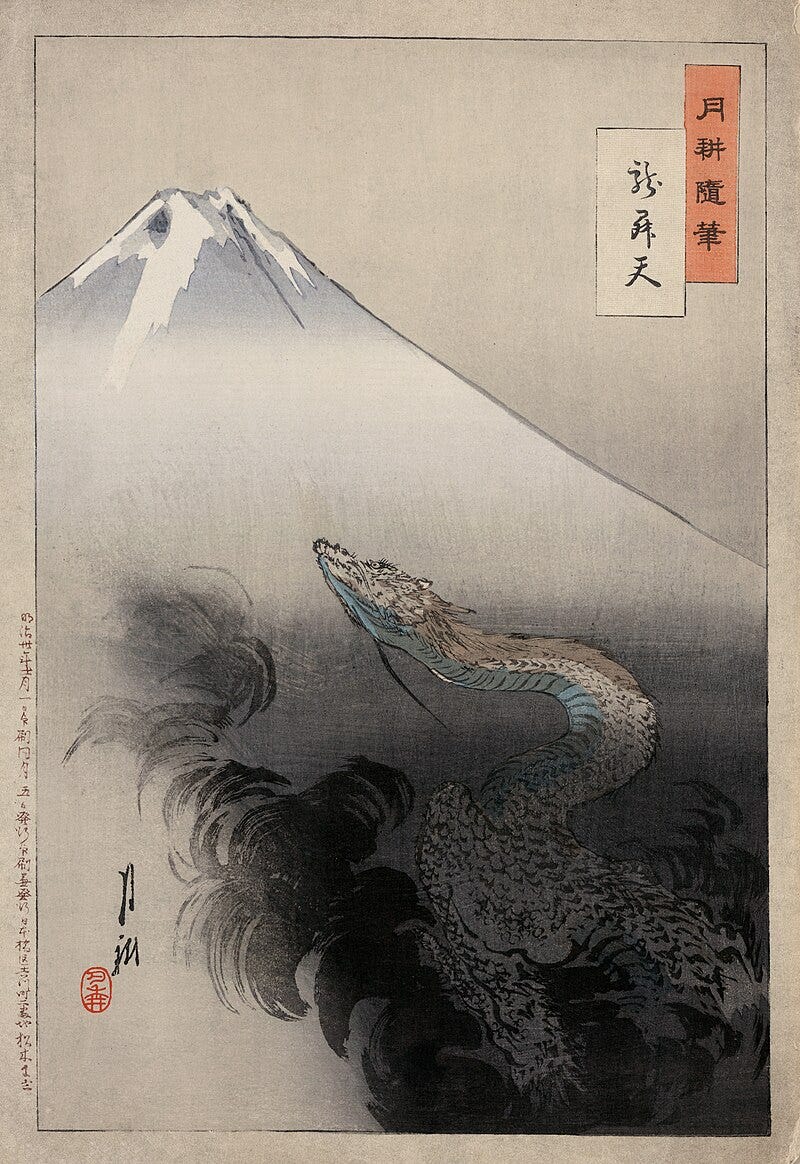

With that, here is the Legend of ‘Anchin and Kiyohime’:

(version taken from Yokai.com)

Long ago, during the reign of Emperor Daigo, the young priest named Anchin was traveling from Mutsu to Kumano on a pilgrimage. Every year he made the journey, and every year he would lodge at the manor of the Masago no Shōji family. He was an incredibly good looking young man, and he caught the eye of Kiyohime, the manor lord’s daughter. She was a troublesome young girl. Anchin joked to her that if she were a good girl and behaved herself, he would marry her and take her back to Mutsu.

Every year Kiyohime waited for Anchin to come again for his pilgrimage. When she came of age arrived, she reminded him of his promise and asked him to marry her. Anchin, embarrassed that she had taken his word seriously, lied that he would come for her as soon as he finished his pilgrimage. On his return, he avoided the Masago no Shōji manor and headed straight for Mutsu.

When Kiyohime heard of Anchin’s deception, she was overcome with grief. She ran after the young priest, barefoot, determined to marry him. Anchin fled as fast as he could, but Kiyohime caught him on the road to the temple Dōjō-ji. There, instead of greeting her, Anchin lied again. He pretended not to know her and protested that he was late for a meeting somewhere else. Kiyohime’s sadness turned into furious rage. She attacked, moving to punish the lying priest. Anchin prayed to Kumano Gongen to save him. A divine light dazzled Kiyohime’s eyes and paralyzed her body, giving Anchin just enough time to escape.

Kiyohime’s rage exploded to its limits—the divine intervention had pushed her over the edge. She transformed into a giant, fire-breathing serpent. When Anchin reached the Hidaka River, he paid the boatman and begged him not to allow his pursuer to cross. Then, he ran to Dojō-ji for safety. Ignoring the boatman entirely, Kiyohime swam across the river after Anchin.

Seeing the monstrous serpent, the priests of Dōjō-ji hid Anchin inside of the large, bronze temple bell. However, Kiyohime could smell Anchin inside. Overcome with rage and despair, she wrapped herself around the bell and breathed fire until the bronze became white hot. She roasted Anchin alive inside the bell. With Anchin dead, the demon Kiyohime threw herself into the river and drowned.

Power, Power Everywhere, but Never a Drop to Drink

You only have power over people so long as you don't take everything away from them. But when you've robbed a man of everything, he's no longer in your power - he's free again.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

When a person spends too long drinking from the fountain of modern ideology, they are often struck with a sort of myopia. That luckless individual will begin to see the motivation for all action, and indeed, the very reason for existence, as being ‘power’. The problem with such an intoxication is this:

When all you see is power, destruction is the only result.

The chasing of power, especially ultimate power, is a perverse motivation in fundamental tales - from Genesis to The Lord of the Rings. If we are to consider that stories, very broadly writ, are applied lessons shown in narrative form, this is how we can apply tales to our lives.

In that spirit, let us imagine a common motif and apply it to reality:

“A man steals a loaf of bread to feed his starving family.”

Now let’s now apply the motivation I’ve outlined above into the example. It’d look like this:

“A man corners the bread market to control the food supply and rule his country.”

Quite different, I’m sure you’d agree.

But are they? Let’s consider the person/people who ‘loses’ in these examples - the baker(s). How does this effect the victim? We can imagine a baker who is on the verge of closing the business; customers are dwindling, the supply of flour is low, the price of eggs have skyrocketed. The baker’s whole life is the bakery, and worse, let’s imagine it’s a legacy business that has been around 200 years - his family honour is on the line.

Does it matter if a megalomaniacal dictator or a desperate father provides the act of theft that breaks the bakery’s back? Either way, the baker suffers.

The obvious ‘answer’ here is that more data is required, in every aspect of the hypothetical. But the point remains: do we focus on the justification, or the overall result?

What is often missed in thought experiments like this is perspective: if we consider the baker as the ‘main character’ in a story, we’d naturally learn more about him. We’d feel more for his plight, in either hypothetical. With the starving father example being discussed, the ‘baker’ is never mentioned. Who says his situation isn’t far worse? Now we have a desperate criminal preying on a downtrodden victim.

Isn’t the allocation of power fun? Who has less, who wants more? It’s a foolish game, ultimately, turning every story into a thought experiment such as this. It is not so much that ‘power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely’, rather, it is more like ‘wanting, discussing, and seeing everything as power dynamics corrupts, and corrupts absolutely’.

This motivation breeds other malign intentions:

Don’t have power but see others wielding it? You seek it.

The hunt for power is ugly, sometimes uglier than wielding it. Having it may cause you to hoard it, resenting people who ask to share it, even to the point of paranoia. More horrors ensue.

You see, there is a certain element of the ‘ink spot on a white linen’ with power. It ruins, even a small amount. Despite not being impossible to avoid, or to repair, it is an incredibly time consuming problem, with a sort of unconscious will to consume everything and everyone. Here’s another way to consider this:

Fire is morally neutral - it can sustain and aid, it can be used to destroy. Water is a good example too - you need it to survive, but too much kills you. Power is more like uranium - it can be used well, but there are other options, and even being near it can kill you.

Is there a lesser-known tale that highlights any of this well?

You bet your power there is.

A big one:

(from ‘The Silmarilion’ by J.R.R. Tolkien)

“In that last battle were Mithrandir, and the sons of Elrond, and the King of Rohan, and lords of Gondor, and the Heir of Isildur with the Dúnedain of the North. There at the last they looked upon death and defeat, and all their valour was in vain; for Sauron was too strong. Yet in that hour was put to the proof that which Mithrandir had spoken, and help came from the hands of the weak when the Wise faltered. For, as many songs have since sung, it was the Periannath, the Little People,dwellers in hillsides and meadows, that brought them deliverance. For Frodo the Halfling, it is said, at the bidding of Mithrandir took on himself the burden, and alone with his servant he passed through peril and darkness and came at last in Sauron's despite even to Mount Doom; and there into the Fire where it was wrought he cast the Great Ring of Power, and so at last it was unmade and its evil consumed. Then Sauron failed, and he was utterly vanquishedand passed away like a shadow of malice; and the towers of Barad-dûr crumbled in ruin, and at the rumour of their fall many lands trembled. Thus peace came again, and a new Spring opened on earth; and the Heir of Isildur was crowned King of Gondor and Arnor, and the might of the Dúnedain was lifted up and their gloryrenewed. In the courts of Minas Anor the White Tree flowered again, for a seedling was found by Mithrandir in the snows of Mindolluin that rose tall and white above the City of Gondor; and while it still grew there the Elder 378 THE SILMARILLION Days were not wholly forgotten in the hearts of the Kings. Now all these things were achieved for the most part by the counsel and vigilance of Mithrandir, and in the last few days he was revealed as a lord of great reverence, and clad in white he rode into battle; but not until the time came for him to depart was it known that he had long guarded the Red Ring of Fire. At the first that Ring had been entrusted to Círdan, Lord of the Havens; but he had surrendered it to Mithrandir, for he knew whence he came and whither at last he would return. *Take now this Ring,' he said; 'for thy labours and thy cares will be heavy, but in all it will support thee and defend thee from weariness. For this is the Ring of Fire, and herewith, maybe, thou shalt rekindle hearts to the valour of old in a world that grows chill. But as for me, my heart is with the Sea, and I will dwell bythe grey shores, guarding the Havens until the last ship sails. Then I shall await thee.' White was that ship and long was it a-building, and long it awaited the end of which Círdan had spoken. But when all these things were done, and the Heir of Isildur had taken up the lordship of Men, and the dominion of the West had passed to him, then it was made plain that the power of the Three Rings also was ended, and to the Firstborn the world grew old and grey. In that time the last of the Noldor set sail from the Havens and left Middle-earth for ever. And latest of all the Keepers of the Three Rings rode to the Sea, and Master Elrond took there the ship that Círdan had made ready. In the twilight of autumn it sailed out of Mithlond, until the seas of the Bent World fell away beneath it, and the winds of the round sky troubled it no more, and borne upon the high airs above the mists of the world it passed into the Ancient West, and an end was come for the Eldar of story and of son.”

Do you feel somewhat cheated, dear reader? You shouldn’t!

Firstly, despite having mentioned The Lord of the Rings earlier, this is from a different book - The Silmarillion - giving us a different perspective on one of the best-known works of literature ever. Secondly, this certainly is a “lesser-known’ tale! Nowhere near as many people have read The Silmarillion as LOTR! Also, don’t feel cheated that I have strayed from sharing written sources chronicling the oral tradition; Tolkien is, in my opinion, the first and, thus far, only person ever to have written a new myth.

So, in conclusion, tough luck 😉

Seriously though, Tolkien drew inspiration from the Nordic sagas, Celtic mythology, and the Kalavela of the Finns, where one can derive the very same overarching theme as found distilled so beautifully in The Silmarillion - when our own weaknesses in motivation turn towards ‘power’ as the ultimate prize, the worst things happen. Indeed, the greatest evil is allowed to grow strong. Tolkien’s focus on this theme is more direct, which is why I chose his text as my example.

Temptation for such a thing as ‘power’ is ruinous. Keep that in mind, if you can.

I’ll try to do the same.

*Ceri immediately calls off the planned land assault of Basingstoke

Well done Ceri, this is very interesting.