Ghosts could walk freely tonight, without fear of the disbelief of men; for this night was haunted, and it would be an insensitive man who did not know it.

- From ‘Tortilla Flat’ by John Steinbeck

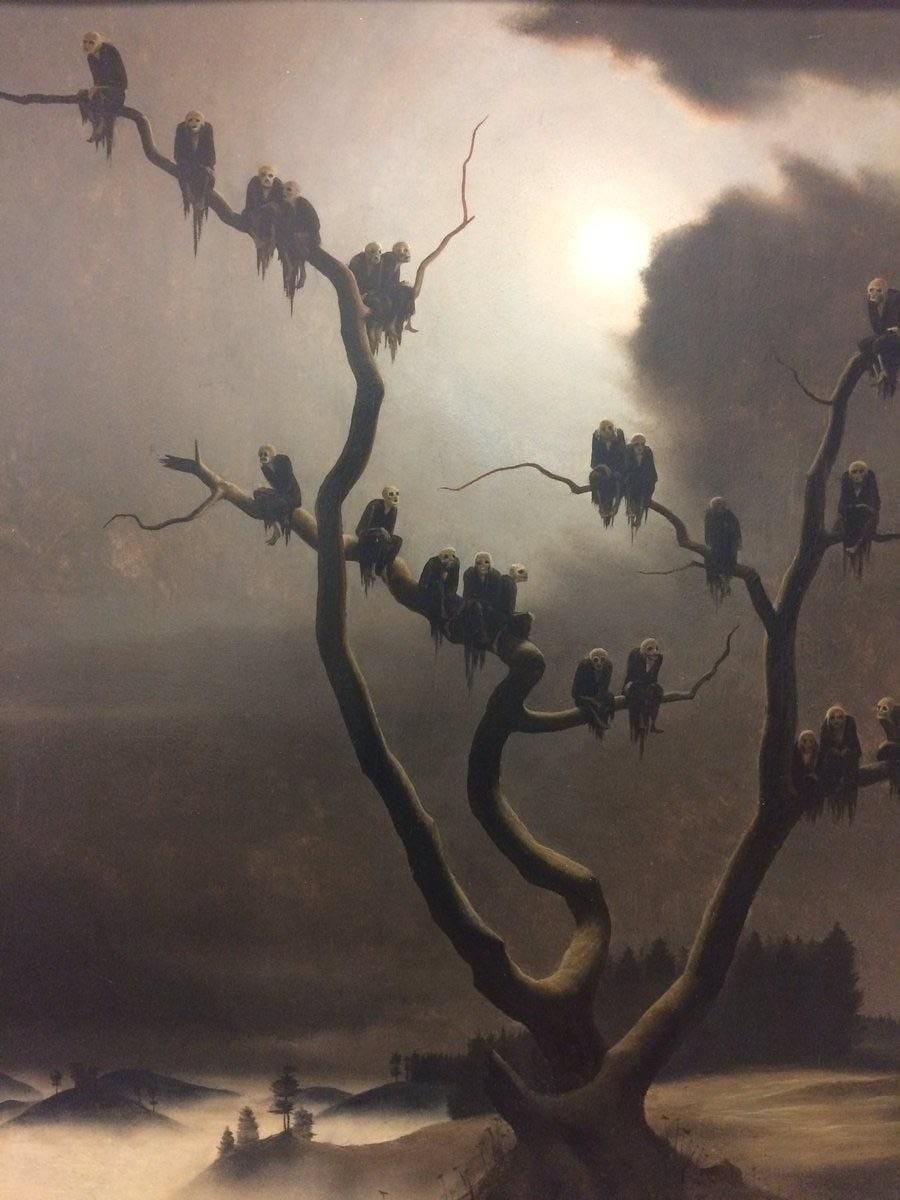

We live in an un-haunted time.

Many thoroughly contemporary, waggish artistes of the written word will claim the exact opposite: “Our era is haunted, a phantom of <INSERT TRENDY ACTIVIST TALKING POINT THAT STRAINS THE METAPHOR HERE> stalks the deserted hallways of the mansion of the now”, or some such nonsense.

No, this day and age is quite singularly ghost-free. We seem to have moved beyond a sincere belief that the dead may have left a trace, or indeed, that they themselves somehow linger on in spirit. Those who do are viewed as the worst sort of outsiders - kooks. And, to be fair, many people who do profess a ‘belief’ in the spirits of the departed roaming this mortal plain are just that - kooks. Worse, there are many profiteering pseudo-kooks, seeking to extract money from the gullible and the desperate kooks they appeal to.

This is why the tales are important - stories are our way to enter the perilous waters of the supernatural safely (alongside the world’s great religious traditions). When we jump in feet-first, without first acclimatising ourselves to the temperature of the waters or, more alarmingly, not knowing how to swim, calamity ensues. Without good training (telling and listening to tales, as humans have done since language began), this is always a risk.

So, in that spirit (pun intended), here are some tales I love telling right now. A ghost, a martyr, and a scientist’s tall tale. Let them be your life preservers in the frigid waters of the River Styx.

That made it sound like I’m just telling ghost stories. I’m not - just the first two - I was just having a bit of a moment. Ghosts will do that to a person, you see.

Enjoy!

The Haunted Merry-Go-Round

Spirit hear me, I am not the man I was.

- Ebenezer Scrooge from “A Christmas Carol” ,by Charles Dickens

Let’s stick with our opening theme at the top here:

Ghost stories are all but gone, but not entirely forgotten. Attacked in the popular media by other, cooler supernatural beasties on one side, and masked manic murderers on the other, the traditional ghost story has been relegated from the heights of our canon of “terrifying tales”, to the lower leagues of “spooky stories (usually for kiddies)”.

Nobody is really scared of ghosts anymore, just titilated at the prospect of contacting one on a reality TV show. And certainly, nobody even gets mildly scared at the prospect of hearing a ghost story.

This isn’t the worst thing ever - I’ve always found the notion of ‘ghosts’ (in European culture, at least) as a perfect concept for allowing emotional exploitation - but I do somewhat lament the waning popularity of the classic, word-of-mouth ghost story.

As with many contemporary problems, I blame the Victorian English: the ghost story was taken as the height of chic entertainment in that era, with many a country-pile-owning family inviting guests over for a séance; you need a good ghost story for a night of holding hands and shaking tables, otherwise it’d be a pretty strange activity! In fact, many of the Victorian-era ghost stories that are found in large houses all over Europe are pretty much the same, adopted for pleasure, devalued and diluted. Once consigned to that most awful place - social cachet - society will inevitably move on to the next thing eventually.

This was the beginning of the end.

Since then, there has been an overarching sense that these sorts of stories are a bit twee, especially the classic English tales (although, this does also seem to be the case across the rest of the Anglosphere, and beyond too).

Japan seems to have retained a sense of horror as the ghost story moves into the digital age, but there will only be so much they can do as that inevitably becomes old hat too. ‘Scary’ was overtaken by an always ‘Scarier’, so moving beyond ghosts becomes inevitable.

This is what happens when a genre gets absorbed by popular media - it becomes a bet laid at the feet of a prospective audience, rather than simply a thing we all used to do.

There are still some short, punchy tales that I love to tell, despite not being a massive fan of the genre. This one from the Netherlands, for instance:

(collected by Alexandra van Kampen)

… this story takes place by the Maas River. One night, a merchant was waiting for a ferry. The oarsman refused to let him cross, saying the headless man was roaming the opposite shore. The merchant joked that without a head this man would have no teeth to bite him with and demanded to cross.

After crossing the river, the merchant continued on foot. He became aware of a gigantic dark shape by his side. It stopped when he stopped and moved when he moved. When he finally dared to face the shape, he saw a five-metre-tall man with broad shoulders and no head. He looked down, and two long horse legs clopped over the ground.

The merchant kept walking, staring straight ahead while the headless men walked by his side. Under his breath, he frantically muttered a prayer. As he finished the words, the headless man disappeared with a loud wail, leaving behind a hellish stink.

See? No ‘lady in white’ or ‘phantom drummer boys’ here! Nor a cursed videotape with the inevitable CGI-boosted drowned girl. There are a few ghost-based urban legends I also tell, but they aren’t enough to renew the tradition fully. Nor am I enough to spur it.

These sorts of tales were once cool, and I really believe they could be again! But if seen solely as a genre for media, old or new, silver or palm-rested screen, it will have to simply wait its turn on the merry-go-round of horror antagonists.

Again.

How can we embed the ghost story in our day-to-day storytelling culture then? It can’t simply be forced - if I, for example, refused to tell any tales other than classic ghost stories to achieve this, it wouldn’t only constrain my practice and career, but would only achieve the formation of a niche audience - popularisation, and cultural embedding, takes time. If you want it to last, that is.

Maybe we need to look beyond European ghost stories, to reimagine the concept of the ghost:

One of the most chilling stories about Ranipokhari involves King Pratap Malla himself. The legend tells of how the king, who had constructed the beautiful pond as a symbol of love and devotion, often visited the island temple located within it for prayer and ritual baths. However, his peaceful visits took a dark turn when he noticed a strikingly beautiful young woman who came to bathe near the temple. This woman, with her enchanting looks and flirtatious behavior, quickly caught the king's attention.

Pratap Malla, known for his romantic liaisons, began a secret relationship with the woman. Their meetings continued for months, though the king's health began to decline. Rumors spread throughout the royal court about the king's mysterious mistress, though no one knew her true identity.

One day, the king met the woman by the pond as usual, but this time, she brought with her a newborn child. She claimed the child was his and, in a horrifying display, strangled the baby in front of the king, stating she had no means to support it. In shock, Pratap Malla looked down and noticed something strange—her feet were backward. Realizing she was a Kichkandi, the king, though terrified, skillfully concealed his fear and continued the conversation as usual before quickly returning to the palace.

Once home, the king called upon a powerful Tantric priest for help. The Tantric, understanding the gravity of the situation, provided the king with a piece of enchanted cotton thread, blessed with powerful mantras. The next day, following the Tantric’s instructions, Pratap Malla returned to Ranipokhari and, during their usual interaction, secretly tied the thread to the woman's garment. After finishing the encounter, the king left, knowing the thread would reveal the Kichkandi’s true nature.

The following morning, the king and the Tantric traced the thread along the edge of the pond. To their horror, it led to a human shinbone lying in a cemetery. The Tantric immediately ordered a funeral pyre to be built, and the bone was burned to ashes, thus breaking the Kichkandi’s hold on the king. From that day forward, the spirit was never seen again, and the king’s health was restored.

Though the Kichkandi was vanquished, Ranipokhari did not remain free of spiritual disturbances for long. According to legend, the spirit of the murdered child—referred to as a balak pisach—began to haunt the area, causing widespread fear. The king once again sought the help of the Tantric priest, who performed a series of rituals to banish the child ghost. During these rituals, the spirit manifested as a ball of rags. The Tantric, using his mystical powers, animated a stone elephant, instructing it to seize the ghost with its trunk. The elephant obeyed, and together with the spirit, was turned to stone.

This statue, located on the south bank of Ranipokhari, remains to this day, showing the stone elephant gripping the spirit of the ill-fated child in its trunk. The story of the Kichkandi and her son lives on in the local lore, though it remains unclear whether the legend was created to explain the statue or if the statue was carved to illustrate the story.

Despite efforts to cleanse Ranipokhari of its supernatural presence, the pond soon fell into disuse. Its eerie history and frequent associations with ghosts and spirits made it an unpopular place for the people of Kathmandu. Over time, the beautiful pond became abandoned, frequented only by those with dark intentions, including those seeking to end their lives. Despite the inscriptions forbidding suicide at the site under threat of severe spiritual consequences, the desolate beauty of Ranipokhari continued to draw troubled souls, further entwining the pond with its legacy of supernatural encounters.

Excellent, don’t you agree?

Well, if you don’t think so, there are still plenty of serial killer legends for you out there. Here’s a classic:

Move Over, St. George

The baby has known the dragons intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon

- from ‘Tremendous Trifles’ by G.K. Chesterton

No matter how reliable the source, no matter how likely they were to have happened, I adore the stories about saints. From Vatican-approved hagiographies to local legends about pre-congregational Welsh hermits, these tales are as close as we get to pure literary fantasy whilst keeping (at least) a toe in the real world.

The following story is my current obsession in this arena:

(from catholic. org, with further links to entries on the site)

Nothing certain is known of her, but according to her untrustworthy legend, she was the daughter of a pagan priest at Antioch in Pisidia. Also known as Marina, she was converted to Christianity, whereupon she was driven from home by her father. She became a shepherdess and when she spurned the advances of Olybrius, the prefect, who was infatuated with her beauty, he charged her with being a Christian. He had her tortured and then imprisoned, and while she was in prison she had an encounter with the devil in the form of a dragon. According to the legend, he swallowed her, but the cross she carried in her hand so irritated his throat that he was forced to disgorge her (she is patroness of childbirth). The next day, attempts were made to execute her by fire and then by drowning, but she was miraculously saved and converted thousands of spectators witnessing her ordeal-all of whom were promptly executed. Finally, she was beheaded. That she existed and was martyred are probably true; all else is probably fictitious embroidery and added to her story, which was immensely popular in the Middle Ages, spreading from the East all over Western Europe. She is one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, and hers was one of the voices heard by Joan of Arc. Her feast day is July 20th.

What is there not to love in this story? It has everything - heroism, drama, tragedy, suspense, and the occasional bit of randomness (her voice was one of those that aided Joan of Arc too?!?!?!)

To be fair, I also love the stories of martyred saints that aren’t quite as fantastical - they can move me to tears - but religious contemplation, study, and consideration needn’t be serious all the time.

Indeed, for me at least, it rarely is.

Accidents Do Happen

It is a good rule in life never to apologize. The right sort of people do not want apologies, and the wrong sort take a mean advantage of them.

- P. G. Wodehouse (being a jerk)

Our final story comes second-hand from the works of Jan Harold Brunvand (who else?). It’s classic urban legend fodder, but begs an important moral question - if one engages in an unspeakably awful taboo without realising, is there any moral culpability to be considered? Before I attempt to answer, here’s the story.

(from ‘Too Good to be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends, Brunvand (2001) - first reported ‘Talking It Over with Wildred R. Woods’ column, Wentachee World, 1987)

I can’t vouch for the authenticity of this story. But Ellis Darley of Cashmere [Washington], retired plant pathologist, says it happened to one of his former colleagues in California.

The colleague, another scientist, grew up in Yugoslavia. During World War II, his Yugoslavian friend experienced severe food shortages, which were alleviated by CARE packages from relatives living in the United States.

The food came in tins. It seems that one package arrived without a label. It was a powder, and the Yugoslavian family assumed it to be a food supplement, which was welcomed at the time.

They tried it out on their meal, found it added zest to the food, and polished off the whole tin.

It was many weeks later that a letter arrived describing the sending of the package.

The letter said that the Yugoslav’s grandmother had died, and that they sent her cremated remains back to her home country in that tin!

Well, she got back home alright.

The notion of accidental sin is something I’ve found fascinating for some time. If full knowledge of a situation isn’t held, how can one be held accountable for misdeeds? Are we to consider that, when accidental, that cannibalism is morally neutral, or good? You see, these questions are predicated on this silly little story being taken seriously. That isn’t to say that we shouldn’t, but it is prudent to consider that stories can often be taken as just that - stories. Not lessons. Not experiments. Just stories.

These stories are older than one may think, and continue to this day. A further note in Brunvand’s entry states:

In 1990 a BBC radio program included a letter from a listener who claimed his family had mistakenly stirred into their Christmas pudding the cremains of a relative shipped back from Australia, eating half of it before receiving a letter of explanation.

A story found in Renaissance sources tells of pieces of the pickled or cured body of a Jew being returned home for burial mistakenly being snacked upon by other shipboard passengers.

In modern times, there are persistent rumours of human flesh being sold as beef.

Grim, I’m sure you’d agree.

Whilst we can take each purported instance in isolation (and, truth be told, probably should), regarding them with due context in order to come to a conclusion. But the concept outlined in the tale - the idea of accidental cannibalism itself - cannot merely be hand-waived as a mere mistake. There is a lesson on imprudence and haste to be gleaned; perhaps a commentary on gluttony, or often, succumbing to thoughtlessness during times of want. It is these times - privation, tyranny, pestilence - that our moral resolve is most tested. Then again, are we to consider this sin as equal to consuming human flesh in full knowledge of what one is doing? Certainly not, I would suggest. Further, should we consider eating a dead relative during a famine (im)morally equal to, say, ritualistically consuming a virgin in order to curse a rival? gain, certainly not.

Not all cannibalisms are created equal, it would seem.

Although these stories are titillating, light-hearted rumours, they hold within them one of the cardinal moral questions - it is, for all my pleas of keeping the stories as stories, unavoidable:

Can a good person remain good in an bad environment?

The answer?

Hey, I’m just a storyteller, do your own bloody answer-seeking

😉