Elvis. Precisely.

On the Importance in Language Choice, Storytelling, and Every Penumbra In-between

If, then, we know what the words mean, a meaning which is found in the purchase these words have in our normal discourse with each other, are people’s intentions secrets we can never discover, hidden behind their words? No, what these intentions are can emerge too in our dealings with each other.

- D.Z. Phillips, my grandfather, from his book ‘From Fantasy to Faith’, 1991

Who are these People? Or Who are these People? Or Who are these people?

Storytelling is a pretty ragged art form when you think about it.

Even with efforts over the last 100 years to de-formalise Art - to ask (what seem like) fundamental questions, to deconstruct, to re-imagine - storytelling seems to already be in that sort of a dissected, or perhaps atomised, position.

Conversely, the folk revival of the early 20th century, with the attendant attempts to both formalise and politicise folk art-forms, only succeeded in creating enclaves of practice that did not supplant the far broader, far older traditions (despite claiming that was what it was itself - yes, mid-15th century folk music sounded exactly like Fairport Convention…🙄). Nor did it kill off the emerging, weirder, new forms of storytelling either, come to think of it. Storytelling has always been diffuse, occasionally manifesting in some very fixed, strict artistic forms within cultures, as well as being simply “a thing some people do” all the time - especially after some absolute genius invented the pub.

Anyway, I’m whittering. Just as a half-decent storyteller should, from time-to-time.

The ‘non-artistic’ forms of storytelling - the rumour, the folk etymologies, the pseudo-histories, the urban legends (yes, I’m working on a show based on these - they’ll soon be considered ‘art’) - are far more subject to slippages of language than the codified artistic mediums. This, in my estimation, is due to the slippery nature of a private conversation versus an artistic work (in our case, a performance); the performer has an air of authority, with an audience there to see what they have to present, whereas in general conversation, there’s a more open environment. Ideas thrive and grow in that place. So do mistakes and misunderstandings.

Most of the myriad data that go into our sensemaking aren’t apparent in the landscape of the casual conversation - etymology, history, the scientific method, etc - it’s wilder that the Wild West, with gunslingers firing their ‘guess what I heard from July’ bullets with a wanton abandon. The good thing is this allows stories to grow; think a snowball rolling down a hill. The problem I haven’t heard anyone discuss is this:

What happens to the abandoned aspects of these stories, the bits and bobs that get omitted, or otherwise changed?

The sad thing about this question is that it is unanswerable - we’ll simply never know. One slippage of language, the whole thing is changed, or worse, gone forever. Or is it that, as the opening quotation suggests, at the very least, the truth will emerge eventually, if not the original wording?

Let’s explore this borderland, and fail together in getting concrete answers.

Folk Heroic

The slippery nature of folklore, and indeed of words themselves, can be used to great advantage, for good and ill, and birth some of the strangest stories we have. Such is the case with my country’s weirdest landmark - The Elvis Rock.

I heard the tale years ago, from a guy who lived in Aberystwyth. He told me that the stone formed the support upon which a down-on-his-luck Elvis impersonator took his own life. This unfortunate man, who came from a small village near the stone, had spent all his savings to travel to Las Vegas back in the 1980s. The man went to compete, hoping to become the world champion Elvis impersonator, but didn’t even place. His dream in tatters, his bank account drained, he returned to his homeland, taking his life whilst resting against the rock:

Some say friends of his wrote ‘Elvis’ on the stone to prove to him that he was the best in their eyes, some say the man himself wrote it before killing himself in order to prove that he was good enough. I’ve even heard a supernatural explanation, claiming that the ghost of the man renews the writing when the paint starts to chip away. If you stay by the rock past midnight, the faint strains of ‘Love me tender’ blow on the wind.

- an acquaintance of mine from Aberystwyth, to the best of my recollection.

All this, of course, is nowhere near why the word ‘Elvis’ is written on this lonely rock in rural Wales. In fact, the real story is no less interesting, and still speaks (broadly) to what we’re discussing:

(from the BBC WALES Blog, James McLaren, 2012)

Just beside the A44 near Eisteddfa Gurig, about 10 miles outside Aberystwyth in mid Wales, you'll see it. In a dip in the road, there's a scruffy-looking rock. On it, stark white letters are painted: ELVIS.

The Elvis Rock has been there for 50 years. Since May 1962 it has been a landmark known throughout the country.

It changes; sometimes it even changes to say something entirely different, but it always reverts, within a couple of days, to the name of The King. But why? Why is it there in the first place? And who ensures it stays there?

In the run-up to the Montgomeryshire by-election held on 15 May 1962, two men in balaclavas decided to demonstrate their support for the Plaid Cymru candidate, Islwyn Ffowc Elis, by painting his surname on a rock beside the road.

John Hefin, from Borth, and his friend David Meredith, from Llanuwchllyn, near Bala, were the culprits.

"It was the 1962 by-election for the Montgomeryshire seat after the death of the Liberal Party's Clement Davies," said Mr Hefin. "We borrowed David's father's car, which was highly recognisable as he was the most respected minister in Aberystwyth, and we took off.

"In balaclavas we set about our task - we wore balaclavas because writing graffiti in those days was very frowned upon.

"We wrote Elis in red and surrounded it in green - the colours of Plaid Cymru and Wales. You could see the sign for at least a mile away in the daylight."

Mr Meredith said of the pair's antics: "We saw this wonderful rock. It's not often that a rock presents itself in such a way and we decided to paint Elis on it.

"We went back some days later to admire our work and damnation, someone had changed Elis into Elvis.

"We never mentioned it to Islwyn Ffowc Elis, but I'm sure he would have been pleased to have been associated with Elvis."

Elis, a politician and novelist, died in 2004 at the age of 79.

Isn’t that awesome? In an attempt to get a Welsh separatist politician elected, these young idealistic men didn’t bargain with the chiefest of Welsh traditions: wonderful humour fuelled by a lack in national self-confidence! This simple act of counter-graffiti, turning a second ‘L’ into a ‘V’, has forged a folkloric tradition all of its own, but more than that, was a barometer for the political will of Wales. Maybe, just maybe, the Elvis Rock was the pivot that kept Ellis from winning his seat! You see, little changes like this reveal a lot, but also play a role in thought itself, and is central to the ineffable way cultures operate.

One slippage, however intentional, can change the course of a nation, and birth a ghost story that never was!

The Adventures of Eggcorn and Lady Mondegreen

Picture yourself on a train in a station

With plasticine porters with looking glass ties

Suddenly someone is there at the turnstile

The girl with colitis goes by- (often misheard and misquoted) from ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ by The Beatles

This section will annoy many of you.

Intensely.

Sometimes changes in the meaning of words and sentences can be unintentional. Honestly, I’d imagine this is probably more common. As we see with the lyrics quoted above, it is often quite funny when this happens. Here are some more slippages:

The term for these types of slippages is ‘Mondegreen’. This derives from an essay penned by the writer Sylvia Wright in 1954, where she refers to a poem that includes the line “and laid him on the green”:

When I was a child, my mother used to read aloud to me from Percy's Reliques, and one of my favorite poems began, as I remember:

“Ye Highlands and ye Lowlands,

Oh, where hae ye been?

They hae slain the Earl Amurray,

And Lady Mondegreen.”… The point about what I shall hereafter call mondegreens, since no one else has thought up a word for them, is that they are better than the original.

These harmless mishaps are funny, speaking to the complexity of linguistics, and the inherent absurdity that stalks the edges of human communication. But the entertaining mondegreen has a far more practical cousin - the ‘eggcorn’:

(from ‘The Eggcorn Database’, written by Chris Waigl)

In September 2003, Mark Liberman reported (Egg corns: folk etymology, malapropism, mondegreen) an incorrect yet particularly suggestive creation: someone had written “egg corn” instead of “acorn”. It turned out that there was no established label for this type of non-standard reshaping. Erroneous as it may be, the substitution involved more than just ignorance: an acorn is more or less shaped like an egg; and it is a seed, just like grains of corn. So if you don’t know how ‘acorn’ is spelled, ‘egg corn’ actually makes sense.

The most quintessential example found in literature comes from the Bard himself (who else?): “To the manner born” from Hamlet is often repeated as “to the manor born”, which in due context, also works.

Isn’t that cool? It’s almost as if God Himself has intervened to aid with all the confusion, retroactively inserting useful meaning back into the errors!

The power found in language is so diffuse so as to be well outside the ‘control’ of any given individual. We must try to be as careful as we can with our use, and our understanding, of language. If we aren’t, we risk getting drunkenly married to the Lady Mondegreen by an Elvis impersonator in Vegas, never to enjoy a delicious eggcorn flatbread again…

Ok, I’ll move on.

(“…The Girl with kaleidoscope eyes” is the correct Beatles lyric, in case you didn’t know)

Teleological Soup

Now for a pickle. Let’s see if it’s a sweet one or a spicy one, shall we?

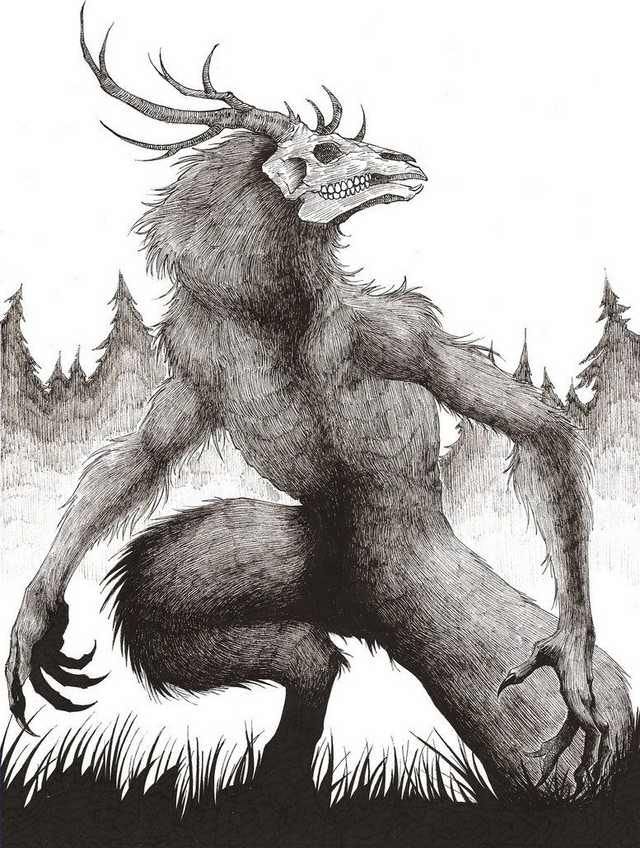

I don’t know where the current popular depiction of the Wendigo came from, but I’ve seen the description of it as a deer-skulled horror B-movie antagonist in many an online ‘story’ and post. This, of course, is nothing like the descriptions found in Algonquian cultures that birthed the tradition.

Now, I’m not going to strain my neck muscles screeching about cultural appropriation, especially since this is not from my culture, but also because there is absolutely no real harm at all in this sort of nonsense.

Cultures are stronger than we give them credit for - this misguided homage (if I am being very kind) won’t do a thing to the cultural life of the indigenous peoples who share the lore of the Wendigo. Satire, for instance, whether from within or without any given tradition, strengthens it rather than weakens it - it is the sign that a culture is healthy, allowing for people to poke fun. These online lore-grabs are similar, in that they exemplify the coolness of the cultures they take from.

Still, it is for many, the new depiction they think of solely when hearing the word ‘wendigo’. With the image comes an explication, just as invented as the pictures. This is the inherent danger in such dabbling.

We cannot ‘stop’ culture, much less common language usage, so these sorts of messy adaptations are bound to occur. But we can point to it, especially when it gets beyond decency, and remind people of what once was. In that spirit, here’s an account drawn from the historical record regarding the wendigo, presented by the excellent Hammerson Peters: