Her lips were red, her looks were free, Her locks were yellow as gold: Her skin was white as leprosy, The Nightmare Life-in-Death was she, Who thicks man's blood with cold.

- From ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, Samuel Taylor Coleridge

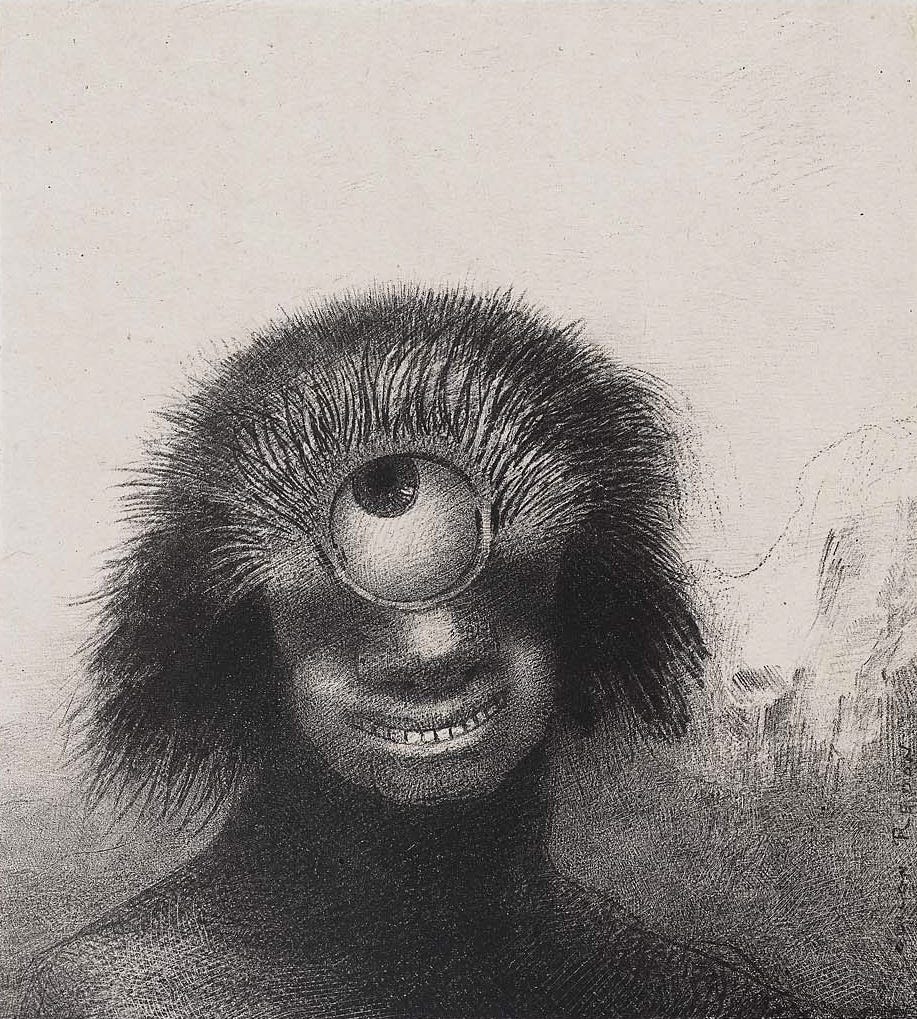

You find yourself alone at night, left by a cab in the wrong place. You’re in a totally unfamiliar part of a city, on an empty street lined with abandoned buildings. A hazy mist swirls about the dim light cast by the street lamps, a light which barely covers a yard beneath the bulbs. The inky darkness seems to emerge from each alleyway, grasping outwards like claws. You walk in a direction you believe is homeward. The air grows oppressively thick as you suddenly feel that you’re being followed. You dare not look back, hoping, praying that it’s just your paranoia, and not some ancient part of your brain that signals for nearby predators. But you cannot help yourself. You swiftly look over your shoulder. Then you see it, lumbering a few paces behind you, a hungry gaze cast upon you. It closes in before you can gather your senses and run, drawing so close you can feel its breath on your face. Smiling, or an expression that reads like a smile, it opens its maw. Only darkness lies within.

It’s a giant duck.

Sorry.

Now, were this reality, that would be utterly terrifying. A 9 ft duck walking behind you, trying to eat you? I’d fill my pants for a 5 ft pigeon!

A vampire, a werewolf, a zombie, some unnamed humanoid figure with elongated limbs, a gaunt face, too many eyes/teeth/tentacles on the other hand - now we’re talking.

Why is the idea of a vampire far more scary to most people than, say, a dragon? A dragon doesn’t have the comical connotation of a giant duck (despite effectively being the same thing, when you think about it), and is still not as terrifying as a vampire - if you tell a child that a dragon will fly over their house that night, they’ll sit at their bedroom window and watch the skies. A vampire? They’ll hide beneath their bedsheets.

I could discuss a great many famous examples from myth and legend here - the cyclops, centaurs, vampires, mermaids - but the classical gets quite a bit of attention. I’m going to try and show you some lesser-known (but not totally obscure) examples of this most spine-chilling group of ghoulish nasties.

We’ll discuss the finer details of this strange phenomenon throughout the article, focusing on the different ways this fear takes shape in traditional, ancient, and contemporary narratives, alongside some possible explanations rooted outside the mythic or folkloric.

We won’t get to a definitive answer, of course, but I will share some of my thoughts as to why a fear of the nearly human is such a part of the human experience. In fact, I’ve found that this subject is so massive in scope that I’ll have to split this into two parts!

I hope to leave you feeling not quite right after reading these pieces, with some tales that won’t just scare you, but also leave needing to go check that your back door is locked… which you should probably do anyway.

I’ll also be dealing with some pretty heavy themes in both these articles, so be forewarned. Monsters, especially those most like us, don’t come about because of anything nice.

Steel yourselves, and enjoy.

To Begin: Terrors From the Deep

We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.- From the poem ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, by T.S. Eliot

From Scotland to South Africa, and everywhere in-between (or to either side… that’s a remarkably straight line I just figuratively drew), you will find stories of supernatural beings that appear as sexy humans (usually women) who then turn into something entirely different.

Something that eats you.

Often these being lurk near waterways or the sea. Sometimes they emerge from the depths of the sea itself, dragging hapless victims to a watery grave. How does this come about?

It may be as simple as: “Dugongs look like people. People often fall overboard and drown. Ipso facto, those watery bints are drowning us”. But our ancestors weren’t that silly, surely?

It may be that simple, it may not. In fact, we’ll probably never know. We must remember: most things presented as a theory are merely hypotheses, and in this case, will probably never get beyond being conjectural.

So what kind of fantastical tales are there about humanoid monsters from dark waters, bubbling up to take a bite out of us?

Well, here’s a tale that explores this, without any sexy transforming people (sorry):

(Translated from Edo Tokyo Kaii Hyakumonogatari by Zack Davisson)

The Kappa of Mikawa-cho

In Kanda, in the vicinity of the town of Mikawa, there was a man named Kichigoro. One late, rainy night he was out running errands for his business when he passed by through the gate leading to Sujikai bridge. There he saw a young boy, about five or six years old, shuffling along the path.

“That is a brave kid to be out like this in the middle of the night…Hey, were are you going?

He asked the young boy, and when the boy turned his face in answer, he saw a face with a swarthy completion, eyes the colour of blood and a mouth that stretched across his face from ear to ear.

Kichigoro was generally a brave man and so even this was not enough to shock him. But when he stretched his neck to take a closer look, the strange creature suddenly jumped into the shadows and disappeared.

Kichigoro flew home as fast as he could where he quickly fell into bed.

“So it seems that the famous kappa does exist after all…”

Short and sweet!

Sometimes a tale exists to simply reenforce a long-held tradition. In this instance, the kappa, the famed water monsters resembling a humanoid turtle, a creature (sometimes a lesser god) that ranges from polite and playful to outright homicidal, reflects how people should behave near rivers: carefully, lest a Kappa emerge and drown you! This short story is as quintessential a folk tale as one can find; it is inferred that people know what a kappa is, and therefore hearing that there has been a sighting is evocative enough for listeners to share worried looks, suggesting that their kids stay away from the river bank beneath the Sujikai bridge from now on. A full-blown narrative, with a beginning, middle, and end? Nah, we’ve heard those!

I’m sure you’d agree that the presence of such a creature is more frightening (and, somehow, more plausible) than the presence of, say, a monstrous fish with a lions head lurking in the depths. Either way, I wouldn’t want to come face-to-face with a monstrous turtle dwarf… despite also wanting to know how one tastes.

They’re also said to love cucumber. The serving suggestion writes itself.

Now for a tale from a bit closer to home. Well, my home at least - I have no idea where you live…. or do I? (I don’t)

For this tale, imagine the humanoid as pale, grey-skinned, diminutive people, about the size of a cat, with saucer-like, yellow eyes, sharp little teeth, and one thick toe on each foot. That’s how I tend to describe the Pwca (roughly cognate to ‘goblins’) when I tell of them. These are the chthonic beings that live beneath the rocky earth, the mountain roots, seamed with coal that once provided Wales with so much wealth (well, the wealth we actually never got… so mainly provided us with silicosis).

Anyway, this story is one I regularly tell!

Enjoy:

(from "Folk-lore and folk-stories of Wales", by Marie Trevelyan, published in 1909)

“The Goblin Stone of Cynwyl Gaio occupied a spot which few people cared to pass at night. In the seventeenth century a young man who had gone far in search of work came in the twilight to a large stone surrounded with grass. The place looked tempting for a night's resting-place. After making a good but simple supper, the traveller placed his bundle containing clothes on the grass in shelter of the stone. For a time he slept soundly, but about midnight he was awakened by somebody pinching his arms and ears and pricking his nose. He got up, and, looking around in the starlight, saw a goblin sitting on the stone, with many others around him. The man tried to run away, but the master goblin would not permit him, and at his command his minions interlaced their grotesque arms around him and prevented him moving. They tweaked his ears and nose, pinched him, gave him pokes in his ribs, and tormented him all through the night in every conceivable manner. He sat down to rest and wait for the dawn, and in the meantime the goblins screamed and laughed and shrieked in his ears until he was nearly mad. When the first streak of morning light appeared, the goblins vanished. The stranger got up in the dawn, and when he went onward he met some workmen, to whom he related his adventure. They said he had slept under the Goblin Stone.”

Now we’ve had a somewhat folksy primer into this particular, peculiar area of storytelling, the rest of this article will focus on what could be the primary source for the monstrous nearly human humanoid:

The notion of the other.

A Parent’s Greatest Fear(s)

Kidnapping causes a long-term rupture in the psyche of those kidnapped and of those who wait for their return. It doesn't end.

- Uzodinma Iweala, Nigerian-American doctor, author of ‘Beasts of No Nation’

There is a universal fear that mankind has that, despite being repeated in tales across cultures, hasn’t really been discussed to the same level as other, ‘big ticket’ fears - death, the dark, isolation, evil.

Abduction.

The phrase “the barbarians are at the gates” evokes in us the idea that these invaders will burn, loot, and victimise those of us inside the city. Seldom do I hear anyone answer: “…and many of us would have been taken away”. There’s more to this fear than being kidnapped, enslaved, or forced to be married.

It is the fear that it will happen to those you love.

This fear turns the abductor into a supernatural monster in the folk canons. Here’s an atypical bogeyman, or in this case, a bogeywoman, from Indonesia:

The Wewe Gombel.

After some light reading online, you’d be forgiven in believing that this character is just another hag motif, a child-stealing, ‘devouring mother’ archetype (yes, sometimes she eats the kids, depending on which part of Indonesia the story comes from).

But there’s more to her. In some areas, it isn;t the kids who should fear her. You see, most bogeymen (and bogeywomen) are designed to strike fear into the child, teaching them not to, say, venture out after dark, or to stay clear of waterways when adult supervision isn’t available. The parents see such figures as a handy, weaponised embodiment of their anxieties, but they typically don’t believe in the bogeyman like the kids. With the Wewe Gombel, as she is portrayed in some areas of Indonesia, it is the parents who need to be afraid!

She will steal away children who are being mistreated by the parents, keeping them safe and treating them well, until mam and dad mend their cruel ways. Sure, she’s a monstrous fiend in appearance, but that only deepens the sense of shame the abusive parents feel; even a tree-dwelling hag monster can raise kids better than them!

It speaks to a deep anxiety many parents feel, coupling it with the very real fear of child abduction - “am I doing it right?”, “does my child like me?”. When this brims over to “WHY WON’T THIS KID SHUT UP FOR ONE MOMENT”, well, this prototypical monster will embarrass you until you learn how to manage your emotions better.

So you’d better learn fast.

Beyond the usual monstrous bogeymen that prudish/worried parents suggest may come and snatch away misbehaving kids, and even beyond this strange Indonesian cousin, there is a monster that goes to terrifying lengths in this regard.

We’re back to Wales for this one, and to a less whimsical corner of our folk tradition. The Plentyn Newid, or in English, the Changeling:

(From The Cambrian Quarterly Magazine and Celtic Repertory , Vol. ii, 1830)

“In the parish of Trefeglwys, near Llanidloes, in the county of Montgomery, there is a little shepherd's cot that is commonly called the Place of Strife, on account of the extraordinary strife that has been there. The inhabitants of the cottage were a man and his wife, and they had born to them twins, whom the woman nursed with great care and tenderness. Some months after, indispensable business called the wife to the house of one of her nearest neighbours, yet not withstanding that she had not far to go, she did not like to leave her children by themselves in their cradle, even for a minute, as her house was solitary, and there were many tales of goblins, or the Tylwyth Teg, haunting the neighbourhood. However, she went and returned as soon as she could. But on her way back she was 'not a little terrified at seeing, though it was midday, some of the old elves of the blue petticoat.' She hastened home in great apprehension; but all was as she had left it, so that her mind was greatly relieved. 'But after some time had passed by, the good people began to wonder that the twins did not grow at all, but still continued as little dwarfs. The man would have it that they were not his children; the woman said they must be their children, and about this arose the great strife between them that gave name to the place. One evening when the woman was very heavy of heart, she determined to go and consult a conjuror, feeling assured that everything was known to him . . . . Now there was to be a harvest soon of the rye and oats, so the wise man said to her, "When you are preparing dinner for the reapers, empty the shell of a hen's egg, and boil the shell full of pottage, and take it out through the door as if you meant it for a dinner to the reapers, and then listen what the twins will say; if you hear the children speaking things above the understanding of children, return into the house, take them and throw them into the waves of Llyn Ebyr (a lake), which is very near to you; but if you don't hear anything remarkable do them no injury." And when the day of the reaping came, the woman did as her adviser had recommended to her; and as she went outside the door to listen she heard one of the children say to the other:

Gwelais fesen cyn gweled derwen;

Gweiais wy cyn gweled iâr

Erioed ni welais ferwi bwyd i fedel

Mewn plisgyn wy iár!(Acorns before oak I knew;

An egg before a hen;

Never one hen's egg-shell stew

Enough for harvest men!)On this the mother returned to her house and took the two children and threw them into the Llyn (lake); and suddenly the goblins in their blue trousers came to save their dwarfs, and the mother had her own children back again; and thus the strife between her and her husband ended.”

The horror of these beings, you will have noted, are twofold - again we have the obvious terror at the child having been stolen away, and the less obvious fear of the otherworldly nature of the creatures in and of itself - to the unfortunate parent, the changeling is an ugly imitation of an infant. a parody, if you will, left to mock them in their pain whilst their child(ren) is gone.

There is an awful, and plausible, suggestion amongst some academics and folklorists as to the origin of such superstitions/tales: before medical science developed to the modern era, and before psychology and psychiatry developed as fields at all, the idea of the changeling may have been a way to explain various disorders, ranging from autism to certain congenital conditions that may cause a child to act in a way that wasn’t ‘normal’. Mental and developmental disorders, and disabilities in general, were not handled as compassionately as we tend to do today - this is one of the generally negative stereotypes of the past that does hold water:

WARNING: DISTRESSING

(From Martin Luther - priest, theologian, father of the Protestant Reformation - on a ‘mentally defective’ child)

“Eight years ago, there was one in Dessau whom I, Martinus Luther, saw and grappled with. He was twelve years old, had the use of his eyes and all his senses, so that one might think he was a normal child. But he did nothing but gorge himself as much as four peasants or threshers. He ate, defecated, and drooled and, if anyone tackled him, he screamed. If things didn't go well, he wept. So I said to the Prince of Anhalt: "If I were the Prince, I should take the child to the Moldau River which flows near Dessau and drown him." But the Prince of Anhalt and the Prince of Saxony, who happened to be present, refused to follow my advice. Thereupon I said; "Well, then the Christians shall order the Lord's Prayer to be said in church and pray that the dear Lord take the Devil away." This was done daily in Dessau and the changeling died in the following year.”

Note how he refers to the child: “…the changeling died…”. The notion that health or mental differences were indicative of not being entirely human, even being inhuman, were long-lived even back in Luther’s time, it seems.

It goes to show that much of what we regard as ‘human’ is tied to our perception of ‘normal’ behaviour and standardised looks. Deviations from this, nowadays (hopefully) do not result in us considering such people as monstrous.

In our past, however, to be the other was to be nearly human.

A Hunger Most Foul

We’ve explored some fascinating beings from the folk traditions so far, some whimsical, some based on prejudices, others conforming to the usual manifestations of a social taboo/anxiety, so I thought we’d explore a creature that is a little of both latter features.

Yes, I’d rather gore and guts than too much whimsy…

The Wendigo has undergone something of a renaissance in the public consciousness of late. Here’s a broad overview, an amalgamation of the traditional tales:

(from my Outline Notes, which cover re-occuring motifs/characters in the folk traditions I cover most often - these entries are used to aid me in being able to discuss the traditions, rather than tell the tales)

“Wendigo: The being started out with a far more supernatural air, with the Cree and Algonquin peoples of the Great Lakes and Canada painting them as a giant, skeletal race that stalked the Boreal Forest of the frozen north. These being could poses people, infecting them with awful dreams. If you suffered one of these dreams, succumbing to the temptation set out by the Wendigo, you would become a creature such as they. What would tempt you as you slumber? a feast of roasted meat. Starvation being a regular worry for the peoples of that land, it may be too much to resist, even whilst sleeping. As you’d bite into the sweet, warm leg of elk meat, a laugh would ring out, shaking snow from the towering trees around you. As you look back down at your meal, you’d notice that it was a human leg that you were tucking into! From that point onwards, no other food would satisfy you. You would hunt for men, women, and most satiating of all, children, never fully able to get your fill.”

“Hold on”, you may be asking “That’s not a Wendigo!”

Maybe you’ve heard the word ‘Wendigo’ described very differently on Reddit, maybe seen it associated with images of strange emaciated night-crawling humanoid monsters in a creepypasta, or a ghostly figure with a deer skull for a head in a low-budget indy horror film?

Ugh.

That’s just the internet doing what the internet does worst, I’m afraid: taking traditional narratives and cutting it down to mere aesthetic, presented back for a cheap, meaningless thrill. The real tradition is deep, pain-ridden, and valuable.

It is also associated with a culture-bound psychogenic illness, referred to as “Wendigo Psychosis”. This syndrome tends to cause sufferers to literally enact the tale as outlined above.

Here’s a grim example that occurred in Canada in the 1870s… or is it proof that those bone giants still cast forth their malign influence from the hidden places of the frozen north?:

Swift Runner's last walk

(Collected and written by Jana G. Pruden in the Edmonton Journal. Sunday, September 18 2011)

It was pitch black and brutally cold when Swift Runner was led from his cell at Fort Saskatchewan jail to start his long, last walk toward the gallows that awaited outside in the swirling snow.

Swift Runner, or Ka-Ki-Si-Kutchin, had been told to prepare for death, and seemed to have heeded the advice. He walked confidently into the yard, seeming much calmer than many of those who were there to watch him die.

Most of the 60 people gathered near the gallows had never seen a hanging, and they were nervous and anxious about what was going to happen. Sheriff Edouard Richard had been delayed by the snow and weather, and was flustered by his late arrival at the fort. The hangman, too, appeared nervous.

The execution had been ordered to take place at 7: 30 a.m. on Dec. 20, 1879. With less than half an hour left to go, it was discovered that the crowd had taken the trap from the gallows and burned it as kindling, that the hangman had forgotten to bring straps to bind the prisoner's arms.

As the sheriff and hangman rushed to get the scaffold ready again, Swift Runner sat near one of the fires that had been lighted nearby, joking and chatting, snacking on pemmican, the thick noose hanging loose around his neck.

"I could kill myself with a tomahawk," he offered, "and save the hangman further trouble."

Swift Runner was well-known around the Fort Saskatchewan settlement, a striking 6-foot-3, with a strapping build and what one policeman called "as ugly and evil-looking a face as I have ever seen."

He had once been known as smart and trustworthy, a reputation that won him a job as a guide for the North West Mounted Police. But, as one newspaper story would later point out: "His contact with white men, however, ruined him."

That ruination came, in part, from an inordinate fondness for the whisky that was smuggled into the area disguised as medicine. Swift Runner was known to be "an ugly customer to meet when on a spree," so ugly that some called him "the terror of the whole region."

The police sent Swift Runner back to his tribe, where he caused so much trouble he "turned the Cree camps into little hells," and was eventually turned out from his community altogether, retreating to the wilderness with his wife, mother, brother and six children.

The police started to hear stories in the spring. A Cree chief said Swift Runner had "turned cannibal," and a hunter reported that Swift Runner's entire family had been killed in the woods, but a squad of officers who went out to investigate couldn't find Swift Runner or his family.

Instead, Swift Runner went to the police himself in the spring, telling them his wife had committed suicide and the rest of the family had died of starvation.

But the officers noticed that Swift Runner didn't look underfed.

"The prisoner arrived at our camp in the spring and did not look very poor or thin or as if he had been starving," one noted.

Suspicious of the story, police travelled with Swift Runner to his family's camp in the wilderness north of Fort Saskatchewan. After days of searching, they found the remnants of a campfire, with piles of bones and human skulls scattered nearby.

Some of the bones were dry and hollow, empty even of marrow. A small moccasin had been stuffed inside the skull of Swift Runner's mother, a beading needle still sticking out of the unfinished work.

Swift Runner was tried for murder and cannibalism by a jury that included three "English speaking Cree half-breeds," four men "well up in the Cree language," and a Cree man who translated the proceedings. A leading CreeEnglish scholar was also brought in to observe the trial and ensure Swift Runner knew what was being said.

Swift Runner sat calmly throughout the testimony of witnesses, who described the family being in perfect health when they headed out to the woods, then Swift Runner coming out of the forest alone.

"He said I could not expect to see any of his family because he was the only one left," said Kis-Sie-Ko-May.

There was no evidence presented in Swift Runner's defence. Asked if he wanted to say anything, he responded: "I did it."

The death sentence was to be the first legal hanging in the Canadian Northwest Territories, an area that includes what is now the province of Alberta. A scaffold was built especially for the execution, and an army pensioner was paid $50 to serve as hangman.

Swift Runner declined to spend the night before his execution with a priest.

"The white man has ruined me," he said. "I don't think their God could amount to much."

Some said Swift Runner had developed a taste for cannibalism years earlier, when he was forced to eat the remains of a starved hunting partner to save himself. Others said he had been possessed by the Windigo, a flesheating spirit that tormented him and gave him nightmares.

Two hours after Swift Runner was led to the gallows, the execution was finally ready to proceed. He was allowed to eat one final pound of pemmican before he was pinioned tightly with rope and taken to the scaffold, where a thick, black hood was placed over his head.

"The trap fell, and Swift Runner went down with fearful force, there being a drop of five feet," the Daily Evening Mercury reported. "He died without a struggle. The body was cut down in an hour and buried in the snow outside the fort."

Sheriff Edouard Richard said those who attended the hanging were satisfied with what they saw.

"Seeing that the Indians are averse to hanging and that all sorts of rumours were afloat amongst them and half-breeds about deeds of cruelty that were to accompany the execution, invitations had been tendered to Indian Chiefs to assist at the execution," he wrote in a report to the government. "Some of them responded to the invitation and declared that it was done in such a way that they could no more object to that mode of execution."

One witness, who had watched several other executions in the United States, also seemed pleased with the spectacle, slapping his thigh and saying, "Boys, it was the prettiest hanging I ever seen."

(more coverage of this case here)

Ooft.

I hope you weren’t eating whilst reading this.

In the next article, we’ll look at disease, blood-draining invaders, and some of the newer lore!

But that’s for next time!

Here’s one last nearly human monster to think about, recounted by the excellent Shrouded Hand (another wonderful Welshman like yours truly). He’ll give you all the tales of this notorious monster from England’s south coast.

Listen closely.

At night.

Alone:

![Carreg Y Bwci [The Goblin stone] Cairn : The Megalithic Portal and Megalith Map: Carreg Y Bwci [The Goblin stone] Cairn : The Megalithic Portal and Megalith Map:](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!cJOi!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffed0cbdc-a91d-4637-a139-1f83e4214a13_300x168.jpeg)